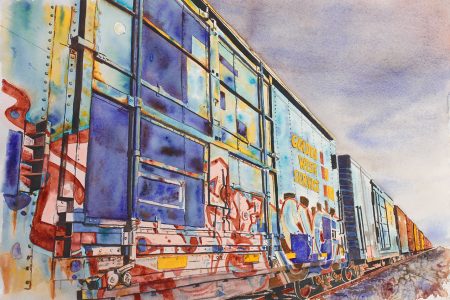

More frequently I am using turquoise pigment in paintings – it depicts so well the effect of weathering by the intense western sunlight on blue-painted surfaces of the subject matter I gravitate to. A few examples:

I’ve also become quite a fan of turquoise (the gemstone) over the years as I travel around Arizona, New Mexico, and Nevada. I tend to seek out turquoise treasures made by Navajo artists, both contemporary and vintage. Moreover, I’ve become kind of obsessed with the different varieties of turquoise – in their greens, blues, and browns – learning about where it was mined, how the local geology affects where turquoise deposits form, and how the geochemistry of the turquoise and its “host rock” affects its appearance once the raw turquoise is cut and polished into a cabochon for mounting in a setting.

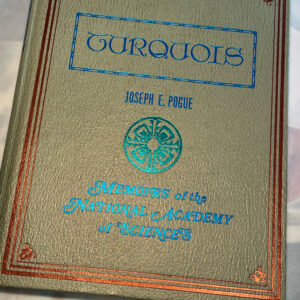

OK, full confession – I studied geochemistry and mineralogy in grad school for my geology degree, so I’m probably more likely to get excited by this than most people. I recently came across a “memoir” of the National Academy of Sciences, simply titled “Turquoise” and originally published in 1915, that I’ve seen referenced in other books and articles on turquoise. It catalogs the occurrence of turquoise mines around the world, describes the mineralogy (hydrated copper and aluminum phosphate, should you wonder), and discusses the origin of turquoise deposits in different geologic settings. Turquoise is deposited from groundwater circulating through the host (existing) rock in an arid environment, and the appearance of the turquoise is a function of the chemical composition of the host rock and the circulating groundwater. Uh oh – GeoNerd alert!

Oh. Where were we? Right, painting with turquoise pigments. So – you might imagine my excitement when I recently was looking to restock some basic turquoise pigment and came across turquoise pigments made from actual mineral turquoise! As opposed to a “synthetic” pigment, these turquoise pigments offered by Daniel Smith are made of authentic turquoise mined from the earth. The photos below show two varieties of turquoise, from the Kingman mine in northern Arizona and the Sleeping Beauty mine in southern Arizona. I’ve painted a swatch (below) that shows the variation in these turquoise pigments. The genuine turquoise pigments – the greenish Kingman and the brilliant blue Sleeping Beauty – “granulate” easily because they’re made of finely-ground turquoise, whereas the synthetic pigment (Windsor-Newton’s cobalt turquoise light) is “laboratory-made” and more uniform in its appearance. Both the granulating and non-granulating pigment have their place, depending on the effect I’m trying to achieve.

So here’s to turquoise! It fits well in my pallet for my southwest-inspired paintings, transports me to the landscape, the people and their art, and lets me wander back into the geology I learned years ago. I hope this helps you further appreciate the turquoise hues in the artwork you admire –